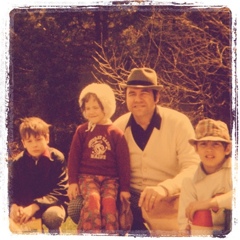

This is the house of my childhood. We moved every five years, but this was the house because it was the last place we lived together as a family. The year we moved away from it, my brother left home for college. And every place subsequent wasn’t quite the same. Our family was never quite the same either, and as my brothers each left home for school and visited later with wives, I came to know that something had been lost to us forever there in that house.

Ours was a town in southern New England, and amidst a backdrop of dense woods, at the end of a long drive, sat our house. It was just past a large, black barrel filled with sand, a barrel put there so that sand could easily be spread when the driveway iced over in those cold months of winter. Having sand on the side of the driveway was handy for keeping folks from spinning out in their cars or slipping in their Sunday shoes. And the chances of falls and fender benders in our driveway were high because our house wasn’t an ordinary house. My father was a pastor, and the house wasn’t ours. We just lived there, borrowing it for as long as the church would have us. Like many parsonages in that part of the country, it sat just behind the church, its driveway a large paved lot for parishioners to park their cars. I wonder at the prospect of a parsonage now, my father rising every morning and walking across the parking lot to his job and then back again at day’s end to his family who waited in a house and life visible to anyone who cared to pay attention. No matter what was going on at the church on any given day of the week, our home sat in the backdrop of every event, meeting and service. Framed and sided though it was, to me it was made of glass and we were an exhibit for hundreds of curious eyes staring past the curtains for a peek at life inside. We were never very far from the honor nor burden of my father’s vocation. As his child in a house owned by his employer, I felt very much the spectacle. It seemed as though everyone wanted to know (because they inevitably asked), “What is it like to be a preacher’s kid?” And when asked, I’d pause and shrug my shoulders before answering, “I don’t know,” looking downward as I had no idea what it felt like to be anything else so had nothing with which to compare my life then.

As much as our lives were exposed, so were others exposed to us for week after week came people to worship services and prayer meetings. They drove down the long driveway in front of our house and settled in a parking space somewhere adjacent to ours. If they ever spied on us, which I doubt they did, we certainly spied on them, from behind bushes and blinds and sometimes from behind the veiled and empty baptismal pool at the front of the sanctuary. There was a man whose suit smelled of moth balls, who would make candy appear from his pockets just for us. Mr. Trabo was his name, and all I remember of him other than his name and his smell is the paper-wrapped, coffee-flavored candy he gave us kids after church. There was the 90-year-old Ernie Catcher who would burn rubber peeling in and out of the church parking lot on Sundays. He used to give kids in downtown Bridgeport rides to church each week but never the same kids twice because after one ride in his car, each would vow never again to put his or her life at risk in the car steered by the led-footed elder in the fedora and mischievous sideways grin.

There was David Moore who was my best friend Mary’s little brother who went to preschool at my mom’s Treehouse Nursery School which she ran in the basement of the church. He contracted bone cancer and died just a few years after we moved away. He’d barely experienced elementary school before his family buried him in the ground. Long after moving away, when I would receive a letter in the mail from Mary and in it that year’s school picture of her, I would marvel at how much older she looked for being still my age, as though more than just her brother was buried that day they all stood around his coffin and finally let him go.

There were the Jurrawicks, our neighbors, who answered my brother’s panicked call and drove hurriedly down our driveway to help me into their car, me with my leg stuck out and my brother’s BB lodged beneath my kneecap. They ferried us to the family doctor, and I’ll never forget how it felt when the nurse unearthed my knee from all the Band-aids the Jurrawicks had conscientiously affixed to my spindly legs that seemed unusually hairy as the nurse prepped my knee for the doctor. I remember the doctor telling me to squeeze the nurse’s hand when his digging into my knee for that BB started hurting more than I could handle. I remember later, after my mom got there, worried and flustered (maybe more for the soul and future of my BB-gun wielding brother than for me), the doctor finally admitting he just didn’t have the tools for the job. And we bandaged that knee again in preparation for the Emergency Room, but this time the area around the BB’s entrance was a small crater from the digging of our doctor. I remember the smiling ER physician with what must have been the right tool popping that BB out in seconds then stitching up our family doctor’s handiwork best he could. I’m not sure, looking back, why our doctor tried so hard to do what he probably shouldn’t have, but knowing that we had no health insurance, I’m sure he was trying to do my parents a favor. That favor decorates my knee still, though no longer the fuzzy, knobby knee of a seven-year-old girl.

It wasn’t just a variety of folks that were exposed to us from within that house, but the most amazing kaleidoscope of colors, the stormy blues of winter ice storms and the giddy depth of fall’s rainbow. The living room window was magical and, through it, I came to identify fall as something only New England knew how to pull off. I’ve never seen fall since the way I remember it as a child. I’ve lived in Florida now longer than anywhere, and I know people who travel north from here, to the closest mountains, and admire the color come October. These seem easily entertained, unaware that brighter, more vivid and resplendent color exists somewhere else. But like any childhood memory, the thing we remember is as much pretend as real. The fall of the present could never live up to the fall of my memories any more than the grown up version of that house and those people could live up to my memory of them. I was a child trying to hold onto one place and one people before my five years came due and the preacher said it was time to move again.

And perhaps that’s true of my entire childhood to that point, up to that day my oldest brother packed his car, pulling out of the parking lot that was our driveway and down the turnpike for New York and with him the smells of the woods behind our house where we made our forts, the roof of the musty pump house where we would aim the front tires of our bikes as we sped down the hill. With that departure went the creek where we floated boats and smashed skunk cabbage, the hiding places in the basement of the empty church, the paths we shoveled in the snow that ended at the back door of the white colonial church that was the perfect icon of the New England of calendar covers.

The day my brother backed his car down that long driveway on his way to college, I watched my childhood grip on place diminish in the horizon of what was next. We would never be together in the way we had been. And when we moved to that next place, we had whittled away in number until at last even my closest sibling had left in search of her own adulthood. Home would become the thing that slipped through my fingers. Though I didn’t feel as old as my friend who watched her little brother suffer only to die in the end, I was already older than I wanted to be, and the rooted carelessness of childhood was already slipping out of my reach.